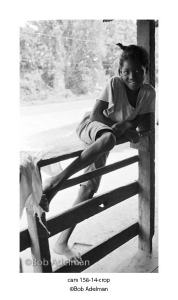

Dan Harrell

Excerpt from This Little Light of Mine, This Bright Light of Ours ©mariagitin2010

Photo ©Bob Fitch 1966

http://www.BobFitchPhoto.com

My boyfriend Bob Block was surprised and didn’t seem especially pleased to see me when we hooked up in Pine Apple. He looked at my legs and shoes and said, “You’re gonna hafta keep up. We don’t have all summer, you know.” That summer, it seemed like every day lasted for an eternity, the way it does when you are a child. But Bob was right, pretty soon the Voting Rights Bill would pass and federal examiners would come help these folks register, backed up by federal troops if necessary. Maybe they wouldn’t need us anymore.

Later, while John G. drove me back to the church before taking Bob down to Lower Peachtree, Bob told me what had happened to him yesterday.

“Dan and I were walking along when this white guy appears out of nowhere. I mean we didn’t hear him comin’, see a truck, nothing. Just like that, he takes his pistol, raises it right to Harrell’s head and presses it against his temple.”

“You know I would kill you as soon as look at you, doncha?”

“I believe I do,” was all that Dan replied.

“Man, that Dan, he was so cool. I was just about to beg and cry myself.”

Bob said as the seconds ticked into years he saw himself just as dead as Dan right there on that country lane, knowing this guy would never be caught or punished.

“And”, Bob explained, “This was just an ordinary guy, not one of the sheriff’s posse or anything, just an ordinary cracker. They can just do this stuff. Man! S–t!” He lit a cigarette and blew smoke out the open car window.

My heart was racing, “How did it end?”

“That cracker just lowered the gun, snorted and spit on the ground and walked away just as fast as he’d appeared.”

Then I told Bob what happened out in Arlington, about being chased all afternoon by a white man in a pickup with a rifle. “He must’ve been related to my guy. Dan didn’t even tell me about what happened with you!”

Bob said, “Yeah, I already heard.”

It made me feel good that our elders knew we were a couple and that he had some kind of idea what was going on with me even if the information didn’t flow both ways. As an eighteen-year old boy he wasn’t the greatest at telling me what I wanted to hear, which was that he’d protect me, no matter what. How could he, when we’d chosen to put ourselves in danger? Being threatened and scared went with the territory and he always claimed he wasn’t afraid. He was likely shell-shocked before I even arrived, what with the tear-gassing, beating and harassment, but he also liked the excitement. That’s a boy for you. I tried to talk and write letters that sounded like my boyfriend Bob, but inside my guts were churning.

There were so many incidents that I can’t recall them all. It was the same all over the South, in every county, every day for years for Movement folks. 95% of them were black folks who pressed on in a mostly nonviolent battle for freedom and justice for all against a continuous onslaught of violence and hatred. Not only were the local grassroots folks the real leaders of The Movement, they saved our little white behinds time and again. Sometimes we knew what they had done and could thank them; sometimes they just kept it to themselves.

Author’s note: Rev Daniel Harrell and his wife Juanita Harrell worked in Wilcox County Alabama on voting rights, literacy and community economic development from 1964 until their untimely deaths, both still in their forties. For more stories of unheralded heroes of the civil rights movement, watch for upcoming publication of “This Little Light of Mine, This Bright Light of Ours” by Maria Gitin. Thank you for sharing your comments and this page with others who are committed to honoring the memory of our civil rights veterans.